Despite all of the excitement of free agent moves and superstars finding new homes for the 2010 National Football League season, the uncapped year that has provided the foundation for all of these moves disguises a damaging potential situation coming about at a high point of the game’s popularity; without a renegotiated collective bargaining agreement between the National Football League and the NFL Player’s Association, there will be no football played after Super Bowl XLV comes to an end on February 6th, 2011.

Now that football is firmly-entrenched as the sport of choice among key American demographics, the league and its players simply cannot afford to have a work stoppage kill their momentum.

Even though I am a sportswriter here, I can’t speak intelligently to the set of agreements and compromises that will need to be reached in order to bring the two sides together to continue football into the future. However, one clear point has been that NFL veterans need to be better compensated, and one way to accomplish that goal is to bring about a new rule: setting a salary cap for rookies that will free up money to be paid to players who have accumulated more time in the league.

This is not to say that Sam Bradford, as the #1 overall draft pick in the 2010 Draft, doesn’t deserve to get a payday for being selected as the St. Louis Rams quarterback of the future. The franchise has no other legitimate option to field a competitive player under center; sure, they picked up A.J. Feeley from the Carolina Panthers this offseason and he brings a veteran presence to the locker room, but he was a 1st-round draft pick nearly 10 years ago and can’t be looked at as anything more than a stopgap at this point. Keith Null–a 2009 6th-round pick for the Rams–put up 3 touchdowns and 9 interceptions in the final three games of the season filling in for departed quarterbacks Marc Bulger and Kyle Boller. If Bradford isn’t suited up to start in Week 1 of 2010, there’s little question that there won’t be much leeway given before he is pressed to take the field.

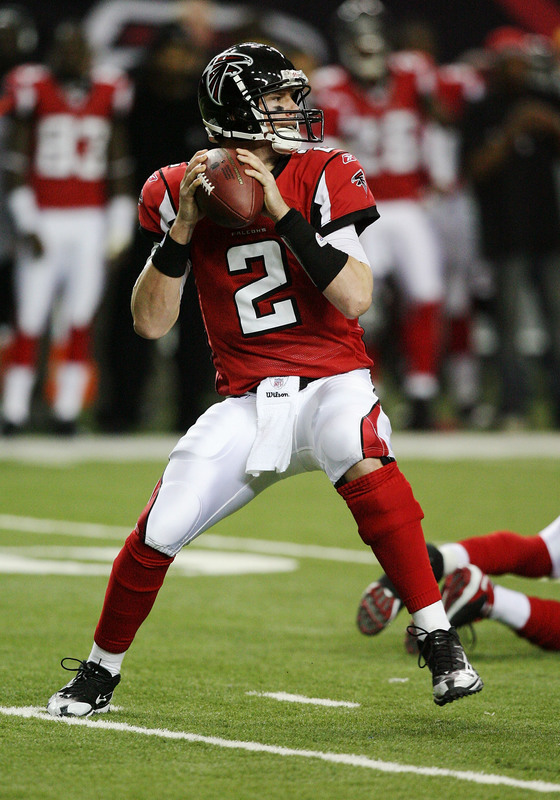

However, the question turns to whether or not Bradford is worth the estimated $50 million contract that is being reported as an early figure in the contract negotiations between him and the team. Though contract talks have not moved along as fast as usual with the first pick of the draft, that number is extrapolated from the contract worked out by the Detroit Lions with their #1 overall draft pick quarterback, Matthew Stafford, in 2009. Stafford got a six-year contract with $41.7 million in guaranteed money and the potential to earn up to $78 million in total. In 2008, offensive tackle Jake Long was taken #1 overall by the Miami Dolphins–even though line players typically make less than quarterbacks anyway, Long still took a five-year contract with $30 million guaranteed and a potential $57.75 million overall. The first quarterback taken in the 2008 draft–Atlanta Falcons QB Matt Ryan–received a six-year contract guaranteeing $34.75 million and being worth up to $72 million. Of course, the selection of quarterback JaMarcus Russell as the #1 pick in 2007 resulted in a six-year contract guaranteeing $31.5 million with a possibility of the deal being worth up to $68 million.

Obviously, these contracts have had varying levels of success. JaMarcus Russell was released by the Oakland Raiders this week after a tenure that can best be described as a failure. Even still, he has already been paid his guaranteed $31.5 million and will end up taking the Raiders for somewhere around $39 million even though he will no longer be suiting up for the team. Despite that investment, Russell put up a record of 7-18 as a starting quarterback–by far the worst record of any #1 overall pick in the NFL. I won’t dwell any further on the statistical evidence of this bad draft selection–mostly because you can do a quick Google search and find multiple analyses yourself–but it is clear that the only person who made out on this deal was Russell himself.

While in many ways the polar opposite of Russell, Matt Ryan’s rookie contract actually made him the fourth highest-paid quarterback in the league before he took a single snap in the pros. Though Ryan rewarded that contract with an Offensive Rookie of the Year season, the concept of putting a rookie quarterback in the top five highest-paid player at the position represents questionable contract practices. In him, the Falcons have a quarterback for the future with a strong upside, but he was injured in key losses last year that kept the team out of the 2009 playoffs. It’s hard to label him overpaid because he brings a great degree of hope to the franchise, but it’s difficult to say that he is more deserving of such a large contract than other tenured veterans–at least at this point in his career. If he “grows into” that contract through strong play over the rest of its duration, Atlanta will have no regrets.

The two contract situations above look perhaps more glaring when one considers New York Jets quarterback Mark Sanchez–selected #5 overall in the 2009 Draft–who helped his team to the 2009 AFC Championship game despite signing a rookie contract of five years with $28 million guaranteed out of a total $50 million contract. Though Sanchez did more to hurt his team’s chances of winning than to help at some points of the season, he found playoff success while making nearly $7 million less than Ryan and about $10 million less than the newly-unemployed Russell.

Based on those numbers, the Jets appear to have gotten away with a steal of a deal compared to the money thrown at other players in recent years. All the same, however, Sanchez can hardly be held solely accountable for his team’s success, and expectations will be astronomical in the coming season; should the results suffer, even his comparatively-restrained contract will come under significant scrutiny.

To address the first quarterback picked in the 2009 Draft–four spots ahead of Sanchez–one need only look to Matthew Stafford’s 2-8 rookie season as a starter for the Detroit Lions. Based on the guaranteed money of the contract, Stafford earned around $6.95 million for a 13 touchdown and 20 interception performance. While he made an impact on the Lions faithful by courageously fighting a separated shoulder to return to the game and throw a last-second go-ahead touchdown against the Browns in Week 11, it is difficult to justify the compensation based on the productivity here. While Stafford still have five years to go on his rookie contract and plenty of time to grow and develop for the NFL, Detroit has made a significant investment here; an investment which may not pay off in the immediate future.

To further put these contracts in perspective, it is useful to compare the free agent money given to two former Pro Bowl quarterbacks who have joined new squads this offseason. Jake Delhomme–who led the Carolina Panthers to Super Bowl XXXVIII–signed a two-year contract with the Cleveland Browns who will end up paying him $7 million to play this season. Though Delhomme is coming off the worst statistical season of his career, that salary puts him just half a million dollars above the yearly salary of guaranteed money given to the Lions’ Matt Stafford before Stafford had played a single professional snap. Former Cleveland Browns quarterback Derek Anderson–sent packing before Delhomme signed–was picked up for a backup role in Arizona with the Cardinals for a two-year contract worth $7.25 million with only $3.25 million guaranteed, despite being a 2007 Pro Bowl selection. Again, in terms of guaranteed money, Anderson is making far less than the rookies of the past few seasons; few would argue that Anderson is worth much more–given his difficulties on the field in 2009–but a career resurgence in Glendale could make this signing a criminal move as well.

Hell; even “Clipboard Jesus”–former San Diego Chargers backup and new Seattle Seahawks backup QB Charlie Whitehurst–landed a two-year backup deal worth up to $10 million despite the fact that he has never thrown a regular season pass though he has been in the league for five seasons. The Seahawks also gave away multiple draft picks to acquire Whitehurst from the Chargers even though they have no evidence of what their new player can do if put on the field in a competitive game situation. Though Delhomme and Anderson both lost the confidence of their teams in 2009, personally I would trust either of them over Whitehurst if the decision was to be made solely on quantitative data.

And herein lies the major motivating factor in setting an NFL rookie salary cap–NFL front offices are willing to throw more money at unproven players than they are at players who are further along in their development. While there are some obvious exceptions–Peyton Manning and Tom Brady don’t go wanting for money even though they are multi-year veterans, while late-round draft picks like the Panthers’ Jimmy Clausen (2010 2nd Round, 48th Overall) and the Browns’ Colt McCoy (2010 3rd Round, 85th Overall) likely won’t be signing large contracts–it would appear that the people in charge of the money are more willing to overpay a youngster with potential than a veteran whose clock is ticking. Aside from that, rookie contracts tend to be longer than veteran extensions; though this makes sense in terms of the wear on an older player’s body, it also leaves a team on the hook if a rookie should end up underwhelming his employers. The financial impact left on the Raiders as an organization through their dealings with JaMarcus Russell would’ve been significantly more manageable had he been given a shorter contract with more money paid through incentives instead of guaranteed in the terms of the signing.

In order to combat the increasing inflation–each successive season seems to drive up the rookie contracts ever higher–of rookie deals, the NFL should restrict rookie contracts to a maximum length of three years and a maximum amount of guaranteed money that is factored based on the average of the yearly salary of the league’s five lowest-paid starting players at that position. This will allow players who have proven themselves in the league to have greater access to their team’s salary expenses while simultaneously sheltering franchises from owing more than they can afford to lose on rookies who do not see their skills translate to the professional level. A three-year contract is a suitable amount of time for evaluating the value of a player–and making a decision on whether or not to maintain their spot on the roster–and it also allows a franchise to make strides towards a long-term contract when the rookie contract comes to a close.

The opposing argument to this idea concerns whether or not a decrease in baseline rookie contracts would lead to further contract hold-outs due to players not feeling as though their skillset is being properly compensated at the professional level. My suggestion for this would be for teams negotiating with rookies to tie extra money to performance-based incentives. Not sure if that sometimes-wild quarterback prospect will be able to rein in his arm at the next level? Give him the baseline rookie contract but promise an extra couple million if they complete a certain percentage of pass attempts while throwing under a set number of interceptions. Feel good about your new defensive tackle but he wants some extra money? Reward him with extra money as he passes certain QB pressure or sack milestones. Draft a new running back who has good speed but a tendency to fumble on short yardage situations? Set up an incentive to reward every few successful 1st down conversions on plays needing 5 yards or fewer to convert. Most professions in the world do not reward underperforming workers by shelling out millions of dollars before seeing results. The NFL should be no different, and the amount of money earned should have a more concrete connection with actual performance.

Based on the current rate of contracts for #1 overall picks in the NFL Draft, we’re looking at the possibility of a guaranteed $100 million contract for the 2015’s draft top selection. In order to avoid such an exhorbitant expense, the NFL and the NFLPA should take the time in renegotiating the next CBA to ensure that rookies are paid a price that is justifiable for a player with no professional experience so that veterans have access to a greater slice of the pie instead of being cut to free agency to make room for the next (unproven) big name.